With war comes much trauma, and America’s Asian wars had the additional consequence of Amerasian children—too often left behind by both parents—who more times than not ended up on the streets. Ther…

- Trang bit her lip. In The Tale of Kieu, the beginning verse of which she had stitched onto the inside of her hat, Kieu sacrificed her own happiness to help her parents and younger siblings. Kieu’s struggle and courage were so remarkable that countless people, including Trang, memorized sections of the 3,254 verses about her life. Could Trang be half as brave as Kieu?

- The previous night, he’d had no doubt that he’d drunk pure water from a gourd. That had been reality. It was his mind that created that reality. The world he lived in, he realized, was created by the mind. That was his insight, and he decided he no longer needed to go all the way to China to study Buddhism.

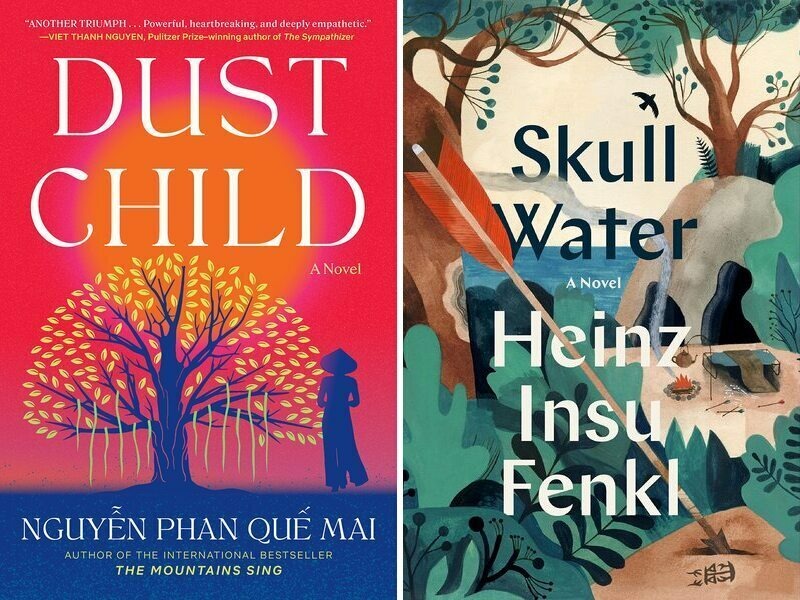

With war comes much trauma, and America’s Asian wars had the additional consequence of Amerasian children—too often left behind by both parents—who more times than not ended up on the streets. There is a term in Vietnamese that translates to “children of the dust” and it’s this concept that drives the story and title of Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai’s second novel, Dust Child. Another recent novel, Skull Water by Heinz Insu Fenkl, also centers around biracial children with GI fathers and Asian mothers during the time of the Vietnam War.

In Dust Child, two sisters move from the countryside to Saigon to help their parents pay off a massive debt after being swindled by money lenders who threatened to take away the land they farmed. Trang, the elder by a year, and Quynh by a year find hostess jobs at a bar thanks to a friend and neighbor named Han. The sisters tell their parents they will be working in an office of an American company, to put their minds at rest, but with their parents’ rising debt the two start meeting men in the bar’s back room. Trang tries to find solace in her favorite book.

Trang bit her lip. In The Tale of Kieu, the beginning verse of which she had stitched onto the inside of her hat, Kieu sacrificed her own happiness to help her parents and younger siblings. Kieu’s struggle and courage were so remarkable that countless people, including Trang, memorized sections of the 3,254 verses about her life. Could Trang be half as brave as Kieu?

Interlaced with this story set in the late 1960s are two contemporary narratives, one from the point of view of a Black Vietnamese Amerasian named Phong and a white couple named Dan and Linda. After being abandoned by his mother and raised by a nun, Phong spends years on the streets with other Amerasians. He fails to obtain a visa to emigrate to the United States and ends up marrying a kind Vietnamese woman and having two children with her. But the trauma from Phong’s childhood—namely from the prejudice he faces due to his skin color—continues to haunt him. The other contemporary narrative tells of a Vietnam vet named Dan and his wife Linda, who suggests a trip to Vietnam in 2016 to help Dan heal from his PTSD.

Dan has his own secrets: he fathered a child during the war with a Vietnamese woman. The stories of these different characters—Trang and Quynh, Dan and Linda, and Phong and his family—all give a human angle to a war that has been historically been politicized in the U.S.

Nguyen Phan Que Mai draws on her doctoral research on Amerasians left behind after the war and her many interviews, while Heinz Insu Fenkl writes from his own experience as the child of a German American GI father and a Korean mother. The title Skull Water refers to a Korean legend during the Shilla Kingdom. When two young monks were traveling to China to learn more about Buddhism, they stopped to rest in a cave. One of the monks drank water from what he thought was a gourd, but turned out to be a skull from a burial yard. Rather than being disgusted, he found enlightenment.

The previous night, he’d had no doubt that he’d drunk pure water from a gourd. That had been reality. It was his mind that created that reality. The world he lived in, he realized, was created by the mind. That was his insight, and he decided he no longer needed to go all the way to China to study Buddhism.

The main character in Skull Water is a young boy with the same name as the author. With his mother’s family he’s known as Insu and with his group of friends—other children of US military fathers and Korean mothers—he goes by Heinz or Fifty-Seven, as in the steak sauce. The novel is a coming of age story set in the mid-1970s while the US military is still in Vietnam. Insu’s father fought in Vietnam, but is back in Korea and recovering from a malaria-like illness in a military hospital. Like Dan in Dust Child, Insu’s father wanted to see the world and joined the military, but could not do that in his home country of Germany. After moving to the US to work on a dairy farm, he was eligible to join the US Army.

Insu and his friends spend their days skipping school and roaming around while their mothers sell goods on the black market. Because Insu’s uncle has been suffering from a hurt foot going back to the Korean war—which the book periodically flashes back to—Insu takes it upon himself to help cure his uncle’s ailment and search for this skull water.

There isnn’t as much suffering in Skull Water as in Dust Child, yet Insu and his family are still haunted by the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and a close cousin’s suicide. And as Insu and his friends soon part—one moves to the US while another just disappears—Insu starts to plan for his family’s own move to northern California.

The damage from war isn’t just in the immediate death, destruction and subsequent trauma in the survivors. It can also manifest in the children born of war, children who are born from military fathers and local women during war that are not always accepted by either side of their families. Skull Water takes more of a nostalgic look at an unusual childhood, while Dust Child shows how trauma can persist over decades until people seek to find any semblance of closure, if possible.