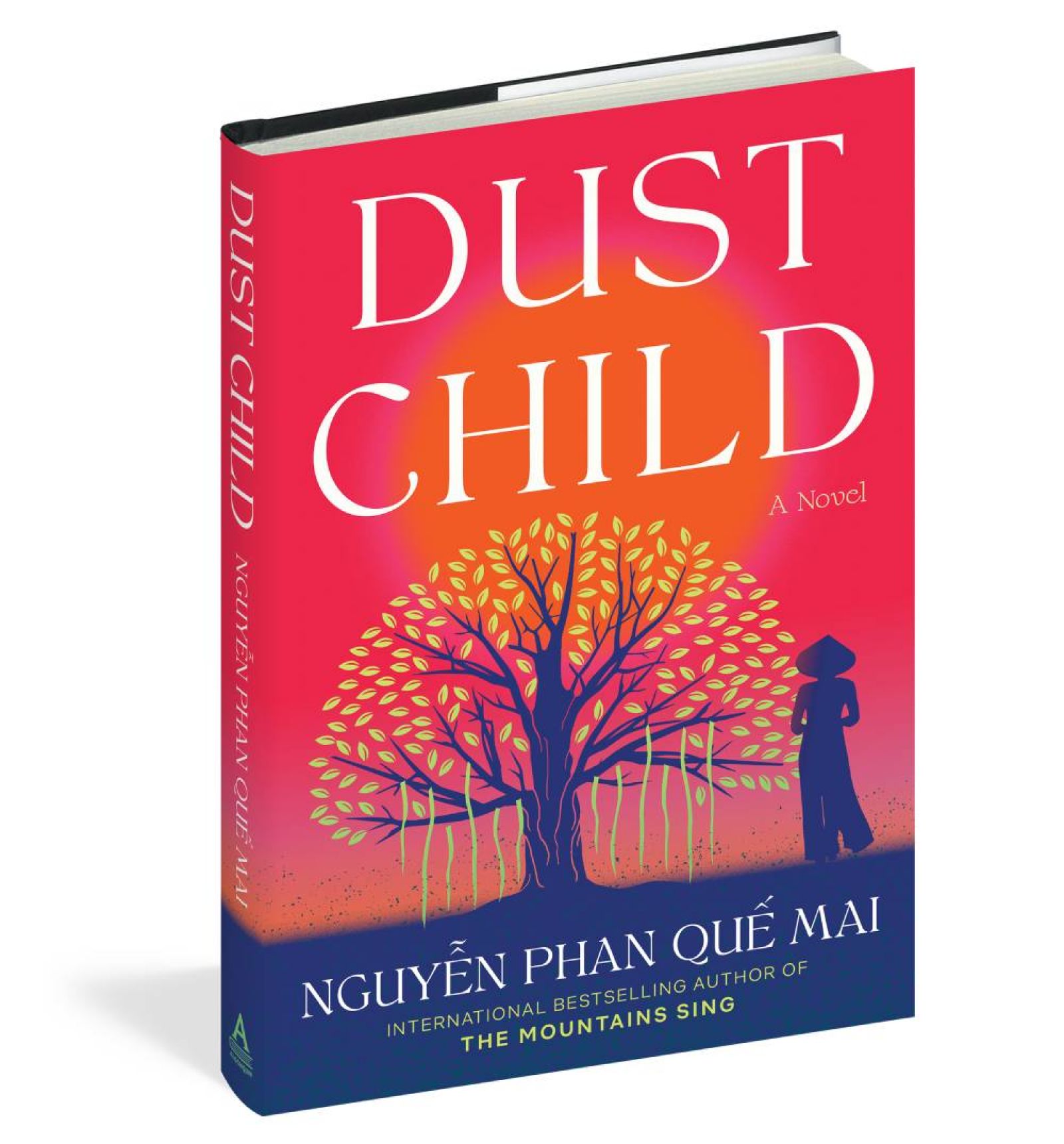

Dust Child portrays the heart-wrenching collateral damage that resulted from a fleeting love during the Vietnam War.

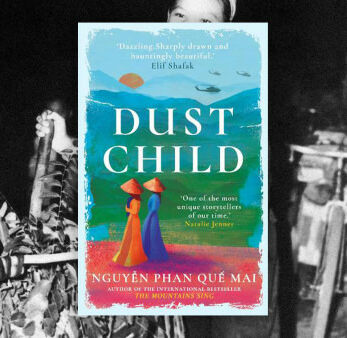

Vietnamese writer Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai’s first novel to be translated into English, the award-winning The Mountains Sing (2020), spun an epic family saga centered on the Vietnam War. Her luminous new novel, Dust Child, is less spacious but still focuses on reverberations from that war. Through intersecting stories of Vietnamese and American characters, Dust Child portrays the heart-wrenching collateral damage that resulted from a fleeting love during the war.

In the opening chapter, set in Ho Chi Minh City in 2016, Phong is a middle-aged man applying for visas for his family to emigrate to the U.S. under a program for children of American soldiers and Vietnamese mothers, so-called Amerasians. Phong’s application is rejected because of a youthful infraction. In later chapters, Quế Mai develops a visceral sense of Phong’s life as an outcast, “a child of the enemy,” a “dust child” who is half Black American, half Vietnamese.

In the book’s second chapter, also set in 2016, we meet Dan and Linda, who are flying to Ho Chi Minh City for a vacation. Linda hopes the trip will help her husband, who was a young helicopter pilot during the war, with his PTSD. Returning to the country for the first time since the war, Dan wants to discover the fates of his Vietnamese girlfriend, who went by “Kim,” and the child he fathered with her, a secret he has kept from his wife for many years.

In the third chapter, set in 1969, we meet 20-year-old Trang and her 17-year-old sister, Quỳnh, working in the family’s rice fields. Crushed by debt from their father’s illness, the sisters decide to go to Saigon to work. They wind up working as “bar girls,” catering to American soldiers, and Trang takes on the alias “Kim” for her work in Saigon’s boisterous Hollywood Bar.

With this setup, the novel’s plot takes on a sense of urgency. How are these characters connected? Will they find one another, and if they do, what will be the outcome? At certain junctures, the plot creaks and shudders as it turns. But Quế Mai provides readers with wonderful linguistic play, and through her deft and illuminating descriptions of the intimate details of her characters’ personal lives and difficult choices, we end up caring deeply for them and hoping for their well-being.

In the novel’s afterword, Quế Mai writes movingly of her research into the challenges of Vietnam’s disparaged Amerasians and how she drew inspiration from the many stories she heard and documented. Through her imagination, she has transformed those stories of dust into something akin to gold.