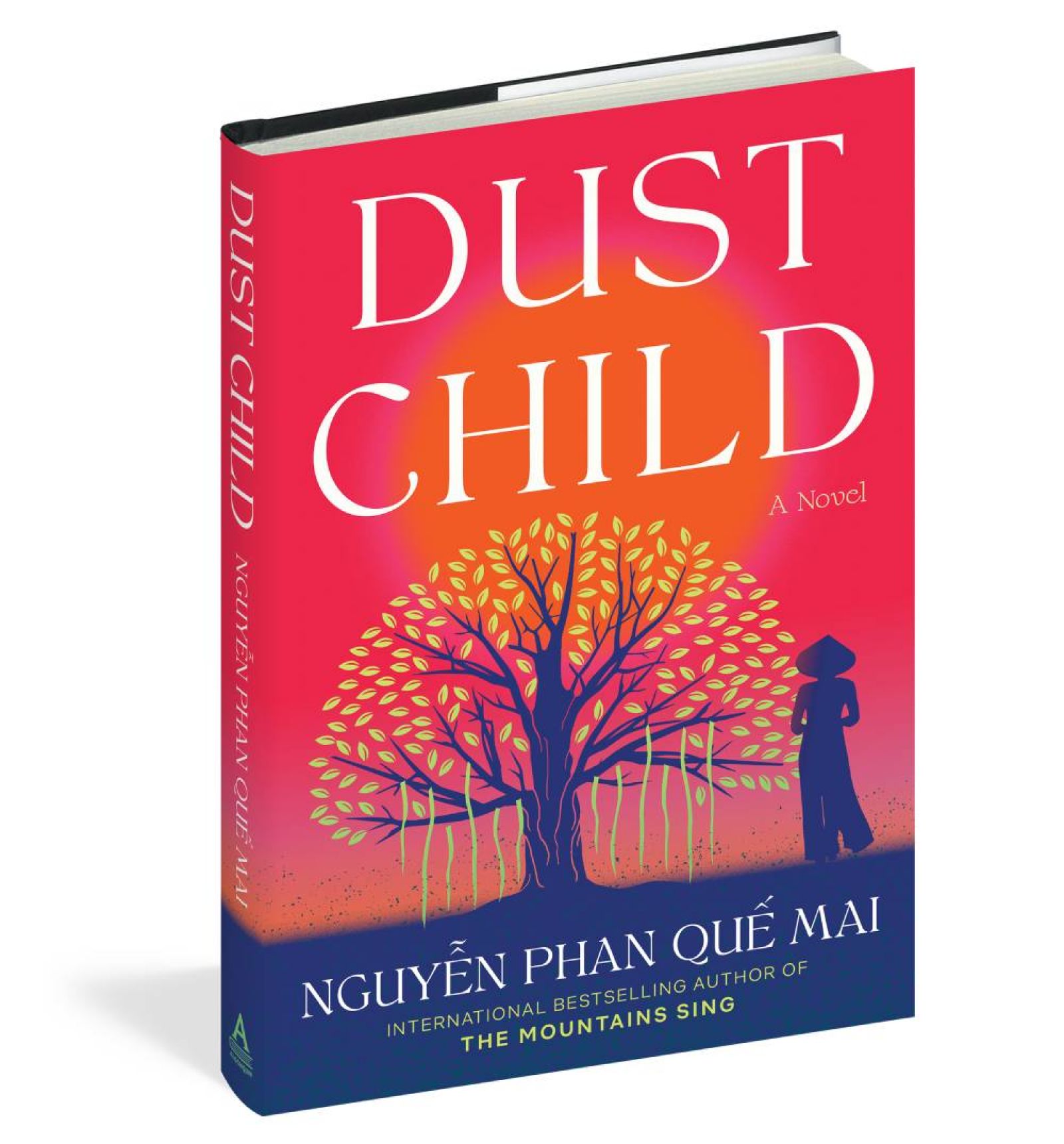

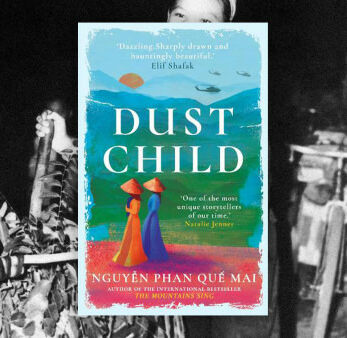

In her moving second novel, Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai writes of about the persecution faced by Vietnamese children fathered by US soldiers

During the Vietnam war, thousands of American soldiers fathered children with Vietnamese women. Little is known about the plight of these Amerasians. Mothers often abandoned their babies, gave them away to orphanages and destroyed any evidence of their relationships with the American servicemen who had returned home. Many Amerasians grew up destitute and were dismissed as “bụi đời” (“the dust of life”). They were persecuted by the Communists because of their mothers’ involvement with the enemy, while those with dark skins suffered racial abuse. Vietnamese writer and poet Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai’s acclaimed debut novel The Mountains Sing (2020) was an international bestseller. Her sophomore, Dust Child, took seven years to write and was inspired by her research into the lives of American veterans and Amerasians for her PhD in creative writing at Lancaster University. Writing in English, Quế Mai interweaves the tales of two young Vietnamese women who become wartime hostesses, a white American helicopter pilot who abandons his pregnant girlfriend and Phong, the titular “dust child”. The dead looked young. Too young . . . As Dan departed the scene in a helicopter, he ‘glimpsed school bags tethered to their bikes’ In 1969, sisters Trang and Quỳnh leave their rural village hoping to find work in Saigon to help their impoverished parents. They are employed by the Hollywood Bar, paid to flirt with American GIs and often pressurised into offering something more. As a mixed-race baby, Phong is left by his mother at an orphanage and brought up by a nun. When his beloved Sister Nhã dies, Phong has to fend for himself on the streets, illiterate and hounded as a “Black American imperialist”. Years later, he applies for a US visa for his family under the Amerasian Homecoming Act, based on the colour of his skin, but is refused. The final interwoven story regards Dan, who lives in Seattle and is scarred by war and plagued by regrets about the way he treated Kim, the hostess he became involved with during his time in Saigon. In 2016, his unsuspecting wife Linda hopes to heal his PTSD by booking a holiday in Vietnam. In an attempt to allay his guilt, Dan decides to try to find Kim and their child. Quế Mai is interested in the personal cost of conflict. She is a skilled storyteller, and her lyrical turn of phrase reflects her characters’ backgrounds as well as their emotions: Trang, for instance, “slept like a rice seedling and woke with a new determination sprouting inside her”. The horrors of war, meanwhile, are conveyed with startling economy. Dan is traumatised by the memory of the schoolchildren his crew gunned down, mistaking them for soldiers: “The dead looked young. Too young. They lay motionless on the ground, their bodies punctured by bullets. Blood has soaked their white shirts, which glistened under the sun”. As Dan departed the scene in a helicopter, he “caught a glimpse of their school bags tethered to the back of their bikes.” The plot strands are drawn together too neatly at the end, but Quế Mai demonstrates a deep understanding of splintered lives. The compassionate treatment of her characters, insights into the period and eloquent prose are impressive.