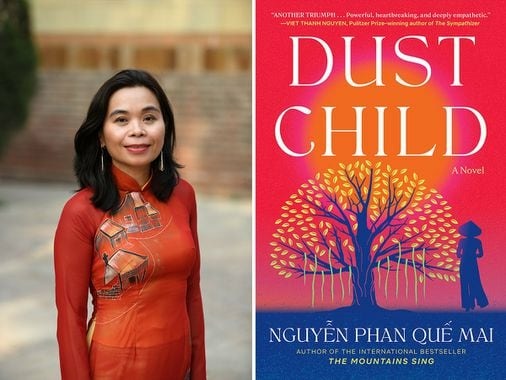

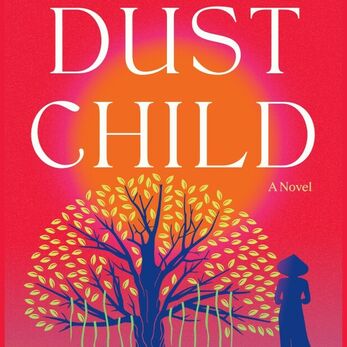

The exquisite novel was sparked by a BBC story chronicling an American vet’s search for his Amerasian child.

It opens in 2016 in Hồ Chí Minh City (formerly Sài Gòn) as Phong and his family wait to speak to American embassy officials. Phong’s father was a Black soldier, his mother Vietnamese, and his origin story was told to him by the Catholic nun who found him.

One night, she tells him, she heard a baby crying. “I paused and listened more carefully. The sound was coming from somewhere in mid-air. … In front of the orphanage stood an ancient Bodhi tree, with hundreds of hanging roots. … That night, I saw a bag dangling from one of the Bodhi’s branches. A sedge bag! … Reaching inside, I felt a baby. Wrapped in a blue blanket, it was as small as a cat, and trembling.”

Despite Phong’s physical appearance and Sister Nhã's story, Phong is rejected for a visa to America, the result of American immigration requirements for Amerasian children to provide documentation of their parentage. Thus Nguyễn plunges readers into the shocking coldness of such policies: The physical markers of their mixed-race parentage made most Amerasians outcasts in Vietnam, but they do not constitute the “documentation” required for proof to enter the US.

She weaves together in silky writing stories that include Dan, a white US vet who returns in 2016, haunted by the pregnant lover he left behind in 1969; Phong, whose story begins in 1972; and sisters Quỳnh and Trang, whom readers meet in 1969 as they work to prepare their family’s fields for growing rice. In a haunting scene, the sisters remind each other how they must act when American helicopters are in the area.

“Trang … managed to survive her encounters with helicopters. Some of them had flown so low that the wind they generated threatened to fling her through the air like a leaf. But she didn’t dare to duck. … Her parents taught her … they shot and killed anyone that ran.” The community dangers to their family are more immediate, however, due to their father’s inability to pay crushing debts. In an effort to help ease that burden, they decide to follow a friend back to Sài Gòn in order to work.

They go to work as Sài Gòn Tea girls, young women who provided American servicemen with company in bars. There, the men buy glasses of tea for the women as payment for conversations and dances. But Quỳnh and Trang are also pressured by their employer to have sex with soldiers in the back of the club.

It was in one of these clubs that Dan met Kim, and as he returns to Vietnam with his American wife, he recalls how he fell in love with Kim and rented an apartment where the pair lived during his off-base hours. But he’s haunted by the way he rejected his pregnant girlfriend, and that guilt lives side-by-side in his head with the PTSD he carried home with him.

While readers may initially suspect that Dan will be the “bad guy,” in Nguyễn’s beautifully rendered portrait, Dan emerges as a complex person, both the frightened 20-year-old piloting helicopters and another casualty of a disastrous war. And yet, Nguyễn never loses sight of the fact that while many American vets have come to be seen as victims, many more victims have been Photoshopped out of America’s historical picture of the war. Giving Dan his full humanity does not block the reader’s view of what the war costs Dong, Kim, Quỳnh, and Trang.

It is one of the many pleasures of “Dust Child” that despite its portrayal of suffering and difficulty, the novel is also infused with joy. Whether writing of Phong’s courtship of the singer Bình, and their eventual marriage, or Kim’s love of poetry, or vibrant street scenes from the cities, Nguyễn beautifully summons the daily lives of her characters.

Which is why moments of suffering hit so hard. They convey just how much war and its aftermath rends the fabric of human life, and how some of those tears cannot be stitched back together. Nguyễn refuses to offer trauma as the vicarious form of entertainment it serves when less-sensitive authors use suffering as bait to provoke sympathy. In telling their stories over a lifetime, she gives each of the characters opportunities to inhabit their full humanity, and chances to learn and change.

|

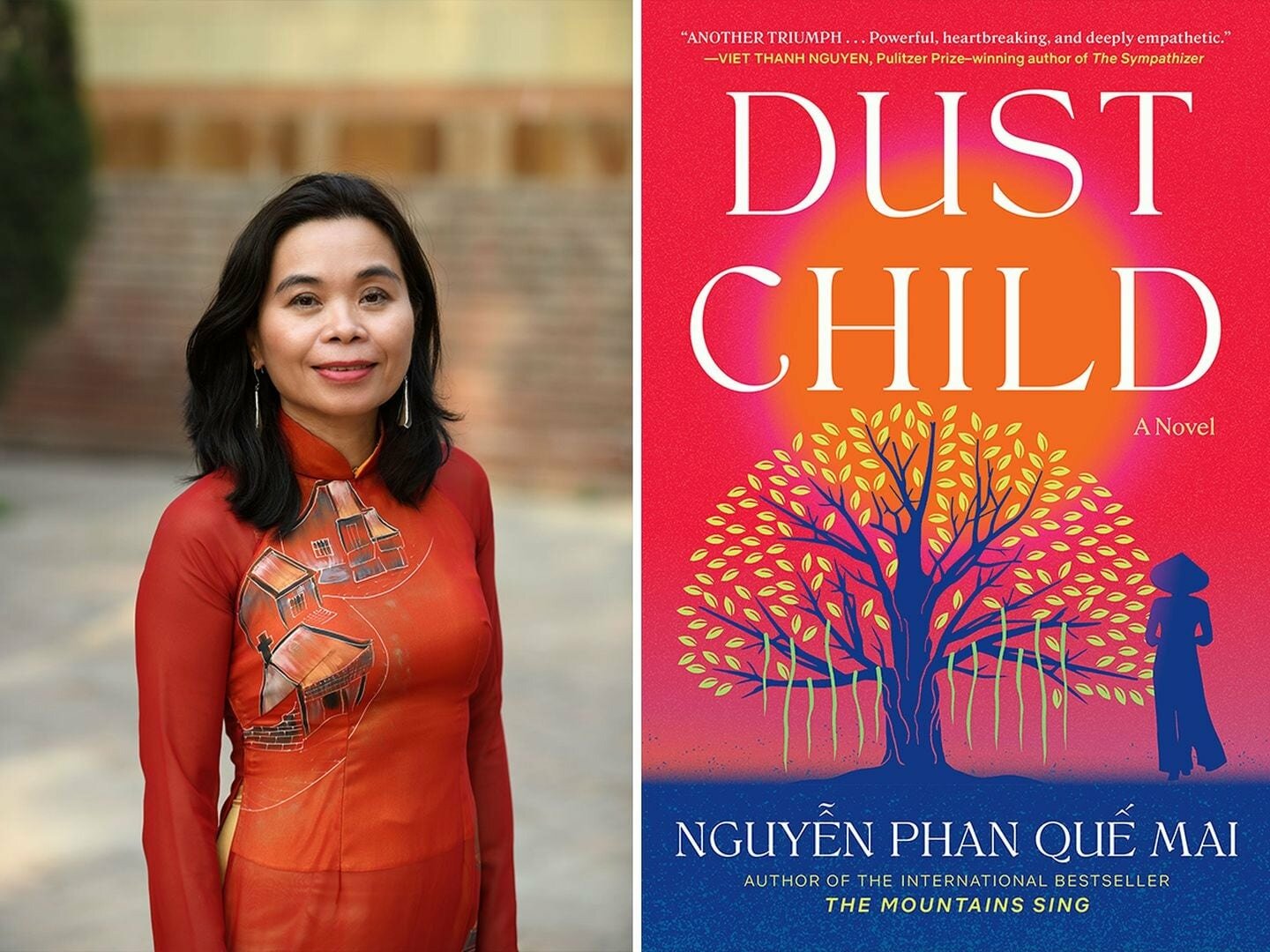

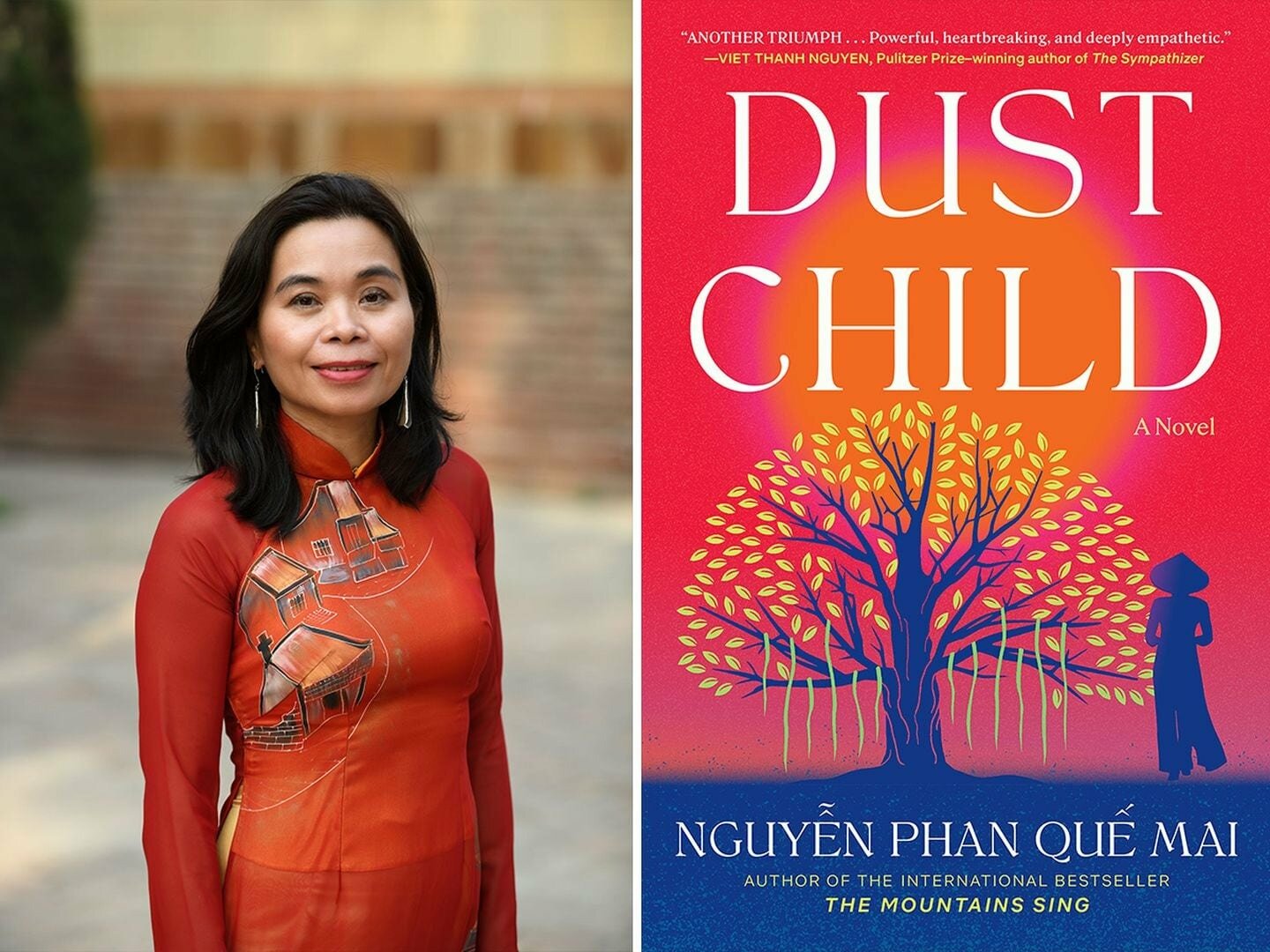

DUST CHILD By Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai Chapel Hill: Algonquin Publishing, 352 pages, $28 Lorraine Berry lives in Oregon. Follow her on Twitter @BerryFLW Get The Big To-DoEnter EmailSign Up |