NINH BINH, Vietnam -- "Just look at this landscape!" my father exclaims to my mother. We are traveling by train from her ancestral village in Nghe An

Novelist witnesses the power of perseverance and family on a poignant homecoming trip

NGUYEN PHAN QUE MAI, Contributing writer

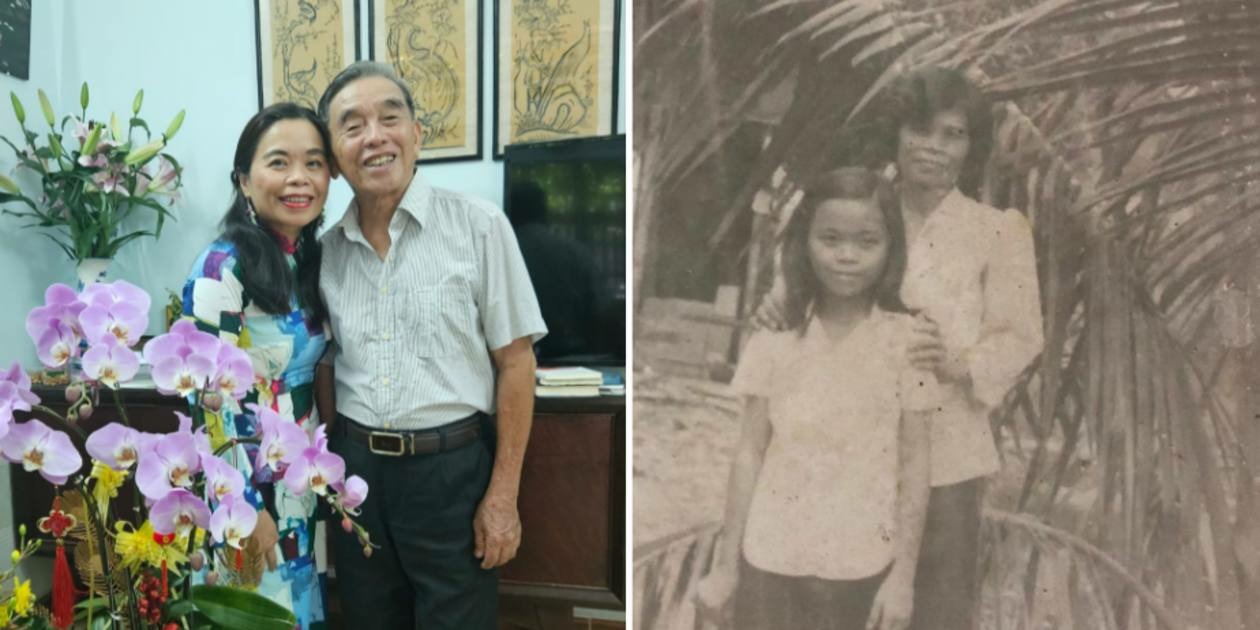

NINH BINH, Vietnam -- "Just look at this landscape!" my father exclaims to my mother. We are traveling by train from her ancestral village in Nghe An province, central Vietnam, to his ancestral village in Ninh Binh province, northern Vietnam. I gaze at my parents, now in their 80s, hair silver-white, yet with smiles as bright as children's as they admire the lush green rice fields, the misty mountains and the winding rivers sparkling in the morning sunlight.I have featured the beauty of my homeland in my novels, poems, essays and short stories, and now I am admiring it through the eyes of my parents, who have lived in southern Vietnam, more than 1,000 kilometers away from their home villages, for the past 45 years.More than two decades earlier, when I lived in Hanoi, two hours' drive from my birthplace in Ninh Binh, my father often told me: "Don't go to our village without me. You would not know how to behave." He feared that I would upset the village's elders by not knowing whom to visit first, whom to invite for dinner, and whose houses I should pass by.Now, my parents are showing the same caution about their own visit. They have been preparing for this return trip for many months. Due to growing fragility in old age, the many obligations they feel they must meet when they return, and the trauma they have tried to bury, they have not visited for many years. For this trip, they have bought new clothes, prepared gifts for our relatives, and set aside cash to pay for reception dinners because those who return from the big cities are expected to finance such meals.In the past, my parents only returned to their home villages if a relative got married, fell ill or died. This time, I have insisted that we undertake a collective journey simply to spend quality time with aging relatives and experience our homeland as tourists.

From Ho Chi Minh City, where my parents live, we flew to Vinh, the largest city in north-central Vietnam, to travel by land to my mother's birth village at Nam Thanh in Nghe An. I was immediately struck by the enthusiastic hospitality of my cousins, who met us at the airport and had cooked many exquisite dishes for a gathering of more than 25 relatives.The next morning, my cousins drove us to Nam Thanh, around 40 minutes from Vinh. My mother became very emotional when we entered the wooden house where she was born more than 80 years before. This house is witness to a terrifying history -- the type of history that I documented in my novel "The Mountains Sing."The property was taken from my mother's family during a land reform program in 1955, when her grandfather was condemned as a "rich landlord" even though he owned only a small piece of land. At that time, following the example of China, the government seized private property and redistributed it among poor or landless peasants before moving to collective farming.The policy caused many injustices because villages and towns were given a quota of "rich landlords" to punish. Even though my grandfather was a hardworking farmer with a modest patch of land, he was beaten and imprisoned, and years later died from related illnesses. His wife had passed away earlier, and when he was imprisoned, his children (my mother and uncles) were driven out of the house by those who took it over. Months later, when my mother's family managed to take back the house, it had been partly destroyed.Our family recently reconstructed the dwelling using the original tiles, pillars, and wooden planks. I never had the chance to meet my maternal grandparents but I grieved for them, and for my two uncles, whose pictures were on the altar. On one of the last occasions when we visited, my eldest uncle, Thanh, had Alzheimer's disease. He could not remember my mother's name. But he remembered vividly the terror of the land reform all those decades ago.

From Ho Chi Minh City, where my parents live, we flew to Vinh, the largest city in north-central Vietnam, to travel by land to my mother's birth village at Nam Thanh in Nghe An. I was immediately struck by the enthusiastic hospitality of my cousins, who met us at the airport and had cooked many exquisite dishes for a gathering of more than 25 relatives.The next morning, my cousins drove us to Nam Thanh, around 40 minutes from Vinh. My mother became very emotional when we entered the wooden house where she was born more than 80 years before. This house is witness to a terrifying history -- the type of history that I documented in my novel "The Mountains Sing."The property was taken from my mother's family during a land reform program in 1955, when her grandfather was condemned as a "rich landlord" even though he owned only a small piece of land. At that time, following the example of China, the government seized private property and redistributed it among poor or landless peasants before moving to collective farming.The policy caused many injustices because villages and towns were given a quota of "rich landlords" to punish. Even though my grandfather was a hardworking farmer with a modest patch of land, he was beaten and imprisoned, and years later died from related illnesses. His wife had passed away earlier, and when he was imprisoned, his children (my mother and uncles) were driven out of the house by those who took it over. Months later, when my mother's family managed to take back the house, it had been partly destroyed.Our family recently reconstructed the dwelling using the original tiles, pillars, and wooden planks. I never had the chance to meet my maternal grandparents but I grieved for them, and for my two uncles, whose pictures were on the altar. On one of the last occasions when we visited, my eldest uncle, Thanh, had Alzheimer's disease. He could not remember my mother's name. But he remembered vividly the terror of the land reform all those decades ago.

Uncle Thanh told me about the vicious shouts and accusations from neighbors and strangers who had driven him and his siblings out of their own house. My mother had told me earlier about the following months when she was ripped from her family -- at 12 years old -- and ended up wandering, in search of a place to sleep and a job to survive.As we prepared our offerings of fruit and flowers and burned incense for my ancestors at the family's altar, I felt my ancestors' spirits, as if they had been waiting for our return. Afterward, I walked around the house, touching the pillars, the doors, the tiles. In the garden, I touched the trees and the flowers; I felt their strength.My cousins drove us to the graves of my maternal grandparents and uncles, which lay at the foot of a nearby mountain range. At my grandfather's grave, I was shocked to be reminded that the tombstone does not bear his real name. His relatives, fearing that his grave would be destroyed by those who had condemned him, gave him another name when he was buried.That name remains on the grave, as if it wants to bear witness to a painful history. After burning incense, my mother asked my cousins about restoring her father's real name on the tombstone, but they said that as some family members had been doing well we should not disturb the grave. They worried that it could bring trouble.In the ensuing days, we visited many of my mother's relatives in her native village and nearby. Some live in houses built by children who have left for better job opportunities elsewhere. Excited by my parents' return, more than 50 of my mother's relatives gathered for a welcome dinner that night. One cousin roasted a large goat in the garden. The night became alive with stories from the past.

Uncle Thanh told me about the vicious shouts and accusations from neighbors and strangers who had driven him and his siblings out of their own house. My mother had told me earlier about the following months when she was ripped from her family -- at 12 years old -- and ended up wandering, in search of a place to sleep and a job to survive.As we prepared our offerings of fruit and flowers and burned incense for my ancestors at the family's altar, I felt my ancestors' spirits, as if they had been waiting for our return. Afterward, I walked around the house, touching the pillars, the doors, the tiles. In the garden, I touched the trees and the flowers; I felt their strength.My cousins drove us to the graves of my maternal grandparents and uncles, which lay at the foot of a nearby mountain range. At my grandfather's grave, I was shocked to be reminded that the tombstone does not bear his real name. His relatives, fearing that his grave would be destroyed by those who had condemned him, gave him another name when he was buried.That name remains on the grave, as if it wants to bear witness to a painful history. After burning incense, my mother asked my cousins about restoring her father's real name on the tombstone, but they said that as some family members had been doing well we should not disturb the grave. They worried that it could bring trouble.In the ensuing days, we visited many of my mother's relatives in her native village and nearby. Some live in houses built by children who have left for better job opportunities elsewhere. Excited by my parents' return, more than 50 of my mother's relatives gathered for a welcome dinner that night. One cousin roasted a large goat in the garden. The night became alive with stories from the past.

The next day, my cousins drove us to the most scenic places in Vinh. Along the way, I admired rice fields rolling out their silky carpets, dotted with storks in flight, the Lam River glimmering in the sun, and the Truong Son Mountains soaring like dragons ready to take flight. Later, we climbed Quyet Mountain to visit the temple of Emperor Quang Trung, famed for uniting the Vietnamese people and defeating foreign invaders.As the sun was setting, I swam in the waves of the immense Cua Lo Beach. My parents, meanwhile, were enchanted by street vendors into buying fresh prawns and squid, which tasted delectable that night after we had grilled them over hot charcoals.Back on the train, heading for my father's native village, I reflected on the village life in contemporary rural Vietnam. The country is developing fast, an investment destination for global manufacturing, but life is still difficult for farmers, many of whom struggle to make ends meet.Soon, we arrived at Ninh Binh train station, to be welcomed by more cousins. We drove an hour from the station to my father's home village, Khuong Du. As soon as we arrived, my father's younger sister and her children rushed out to welcome us. We burned incense for our ancestors and visited the surrounding rice fields where my relatives are buried.I knelt next to my paternal grandmother's grave -- which we only found 65 years after her death. She died in the Great Hunger of 1944-45, when Vietnam was occupied by Japanese and Vichy French troops during World War II. The famine killed nearly 2 million people, almost 10% of the population at that time. Three of my family members perished, and my father's uncle is still missing, having left home in search of food.

The next day, my cousins drove us to the most scenic places in Vinh. Along the way, I admired rice fields rolling out their silky carpets, dotted with storks in flight, the Lam River glimmering in the sun, and the Truong Son Mountains soaring like dragons ready to take flight. Later, we climbed Quyet Mountain to visit the temple of Emperor Quang Trung, famed for uniting the Vietnamese people and defeating foreign invaders.As the sun was setting, I swam in the waves of the immense Cua Lo Beach. My parents, meanwhile, were enchanted by street vendors into buying fresh prawns and squid, which tasted delectable that night after we had grilled them over hot charcoals.Back on the train, heading for my father's native village, I reflected on the village life in contemporary rural Vietnam. The country is developing fast, an investment destination for global manufacturing, but life is still difficult for farmers, many of whom struggle to make ends meet.Soon, we arrived at Ninh Binh train station, to be welcomed by more cousins. We drove an hour from the station to my father's home village, Khuong Du. As soon as we arrived, my father's younger sister and her children rushed out to welcome us. We burned incense for our ancestors and visited the surrounding rice fields where my relatives are buried.I knelt next to my paternal grandmother's grave -- which we only found 65 years after her death. She died in the Great Hunger of 1944-45, when Vietnam was occupied by Japanese and Vichy French troops during World War II. The famine killed nearly 2 million people, almost 10% of the population at that time. Three of my family members perished, and my father's uncle is still missing, having left home in search of food.

We came home to a large dinner in my aunt's front yard, where relatives from near and far gathered to welcome us. They told me tales about my parents, how my mother had come here to work as a teacher, and how she had met my father when American airplanes were dropping bombs onto our province.Sitting in the front yard, I cast my eyes out to the garden, where I had played hide and seek in my family's bomb shelter, which my father had dug under a bamboo grove. The shelter had protected my family during raids by French and Japanese troops, as well as American bombings, and now it was gone, replaced by a plot for sweet potatoes.Tears welled in my eyes as I thought about my grandfather, who taught me how to hide in the shelter should the bombs return. He was the only grandparent I knew, and he took great care of me and my brothers. He died when I was young, and at dinner that night, my father asked me to read my poem for him. I read my poem for my grandmother, too: "My hands lift high a bowl of rice, the seeds harvested in the field where my grandmother was laid to rest./Each rice seed tastes sweet as the sound of lullaby from the grandmother I never knew."

We came home to a large dinner in my aunt's front yard, where relatives from near and far gathered to welcome us. They told me tales about my parents, how my mother had come here to work as a teacher, and how she had met my father when American airplanes were dropping bombs onto our province.Sitting in the front yard, I cast my eyes out to the garden, where I had played hide and seek in my family's bomb shelter, which my father had dug under a bamboo grove. The shelter had protected my family during raids by French and Japanese troops, as well as American bombings, and now it was gone, replaced by a plot for sweet potatoes.Tears welled in my eyes as I thought about my grandfather, who taught me how to hide in the shelter should the bombs return. He was the only grandparent I knew, and he took great care of me and my brothers. He died when I was young, and at dinner that night, my father asked me to read my poem for him. I read my poem for my grandmother, too: "My hands lift high a bowl of rice, the seeds harvested in the field where my grandmother was laid to rest./Each rice seed tastes sweet as the sound of lullaby from the grandmother I never knew."

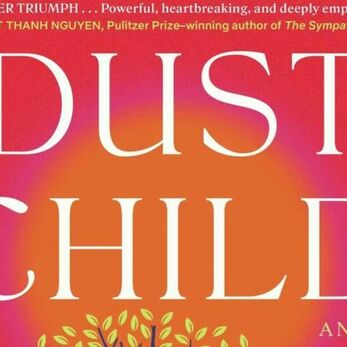

In the many conversations with my relatives in the ensuing days, we did not talk about loss and pain, but about the work and studies of our children and grandchildren and the sad truth that most young people now have to leave our home village to find better opportunities because of the lack of local employment.Before our departure, I took my parents around Ninh Binh province, and we were astonished at how tourism has progressed. The area has become a major tourist site, attracting millions of local and international tourists every year. At Trang An and Tam Coc, my parents and I sat back as our sampans glided on the emerald waterways, transporting us into long, mysterious caves, letting us pass under tall, majestic cliffs, along vast green fields and patches of blooming lily flowers.Ninh Binh city was Vietnam's first capital, and is the home of the Trang An Complex -- a UNESCO World Heritage Site. I am reminded of its historical, cultural and environmental significance as we visit Hoa Lu Old Town and the stunning Bich Dong Pagoda and see the many wild birds at Thung Nham Bird Park.My aunt cried when she said goodbye to us. I promised to return. And I need to, often, in the stories that I will write. Stories that will help us remember, and to heal.Nguyen Phan Que Mai is an award-winning Vietnamese poet and novelist, author of the international bestsellers "The Mountains Sing" and "Dust Child"

In the many conversations with my relatives in the ensuing days, we did not talk about loss and pain, but about the work and studies of our children and grandchildren and the sad truth that most young people now have to leave our home village to find better opportunities because of the lack of local employment.Before our departure, I took my parents around Ninh Binh province, and we were astonished at how tourism has progressed. The area has become a major tourist site, attracting millions of local and international tourists every year. At Trang An and Tam Coc, my parents and I sat back as our sampans glided on the emerald waterways, transporting us into long, mysterious caves, letting us pass under tall, majestic cliffs, along vast green fields and patches of blooming lily flowers.Ninh Binh city was Vietnam's first capital, and is the home of the Trang An Complex -- a UNESCO World Heritage Site. I am reminded of its historical, cultural and environmental significance as we visit Hoa Lu Old Town and the stunning Bich Dong Pagoda and see the many wild birds at Thung Nham Bird Park.My aunt cried when she said goodbye to us. I promised to return. And I need to, often, in the stories that I will write. Stories that will help us remember, and to heal.Nguyen Phan Que Mai is an award-winning Vietnamese poet and novelist, author of the international bestsellers "The Mountains Sing" and "Dust Child"

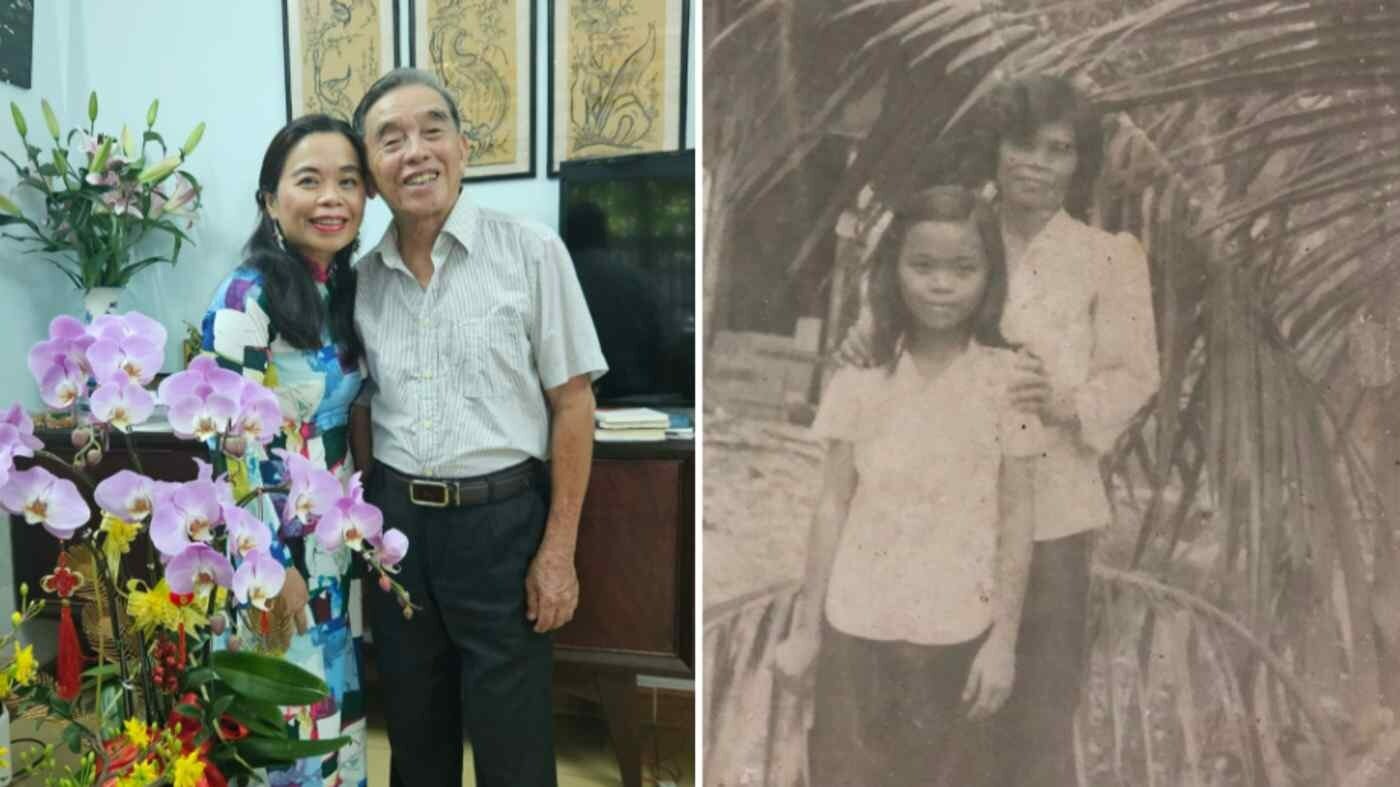

Que Mai and her parents. (Courtesy of the author)

The house where Que Mai's mother was born. (Courtesy of the author)

Que Mai with her cousins in Nghe An, the central Vietnamese province that is home to her mother's ancestral village. (Courtesy of the author)

A farmer and his water buffalo pass by. For many in contemporary rural Vietnam, making ends meet is not easy. (Courtesy of the author)

Top: Many relatives in Ninh Binh welcomed the author's family back. (Courtesy of the author) Bottom: The author in traditional Vietnamese attire. (Photo by Tapu Javeri)