As I write this inside my apartment in Jakarta, Indonesia, the sounds of ambulances blaring through our closed doors and windows put me more on edge. I am waiting for my visa so I can evacuate with…

As I write this inside my apartment in Jakarta, Indonesia, the sounds of ambulances blaring through our closed doors and windows put me more on edge. I am waiting for my visa so I can evacuate with my German husband and our son to his homeland, where we can be reunited with our daughter. The trip from one coronavirus hot spot to another will be long and risky, but I need to be near our daughter and hold her tight.

Article continues after advertisementRemove Ads

Perhaps my fear and anxiety have roots deeper than the coronavirus pandemic: the death, devastation and separation I experienced as a child, and later, my family’s search for safety during the resulting displacement. These feelings make me long for my own homeland—Việt Nam—where my parents and brothers live. As I cannot travel there to be with them now, I need to let my writing bring me home.

And I am home now, laying on a hammock, listening to my mother’s lullabies and the ca dao songs that rise like colorful kites above the green rice fields of my home village in Ninh Bình. I am home, playing hide and seek with my friends by crawling into a secret shelter my grandfather dug under the bamboo grove behind our garden.

Coiled up, I embrace the dark, cool shelter which protected my family from invading French and then Japanese troops and, eventually, American bombs. I belong to my village’s soil and the bamboo’s thorny, resilient roots.

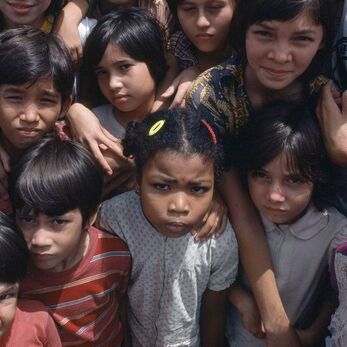

I am home, running barefoot on the village dike. As I fly my kite, catch grasshoppers and jump rope, I recall how that dike supported slim, motionless women. Their eyes remained fixed on the dirt path which zigzagged through fields from the main road. Years later, I learned that the women were waiting for the men who went missing during the war that ravaged my homeland for nearly 20 years, killing more than three million people. The fighting ended April 30th, 1975, two years after my birth, but for many of my countrymen, the war would not end.

Article continues after advertisementRemove Ads

I am home, floating on the village pond, kicking my legs furiously, holding onto a banana trunk, believing that I can swim after having let dragonflies bite my bellybutton. It is the same banana trunk that carries me as I slide down the village road which becomes a river of mud during a rainstorm. The road I filled with so much childhood laughter was also where my father witnessed American bombs take the lives of his best friends and my mother narrowly escape death.

On the train journey that takes me thousands of kilometers down Việt Nam, I see such darkness, light, sorrow and hope through a child’s naive eyes.

I am home, boarding a buffalo cart the summer night when I was six years old, surrounded by our few pairs of clothes, bowls and chopsticks, cooking pots and pans. Just a few days before, my parents told me they had decided to uproot our family and plant us in a new garden in southern Việt Nam. They said that in Bạc Liêu, a small town situated at the Southern tip of the Mekong Delta, storms would not destroy our harvests like in Ninh Bình.

There we would have enough to eat, and most importantly, my two brothers and I would have a chance to go to university one day. As the cart pulls away, I look back at my village—a blanket of darkness dotted by tiny eyes of oil lamps. I learned later that in darkness there is light, in sorrow there is hope.

On the train journey that takes me thousands of kilometers down Việt Nam, I see such darkness, light, sorrow and hope through a child’s naive eyes: in the gigantic bomb craters that war bit into the earth; in the emerald fields dotted by grazing buffaloes and farmers whose backs bent low above the rice; in majestic mountains, rolling beaches, deep blue ocean; and in the Hiền Lương bridge which slings its skeleton over the Bến Hải River that once slashed my country in two.

Once I arrive in the south, my homeland is the rice, green beans and sesame seeds my family harvested on a patch of land that had been used as a shooting range by the Southern Vietnamese Republic’s Army. I touch war and death by way of the cold metal of unexploded bullets and shells which I used to dig out of the earth to make space for our crops to grow. These bullets and shells helped me earn money for our meals and my school fees.

Article continues after advertisementRemove Ads

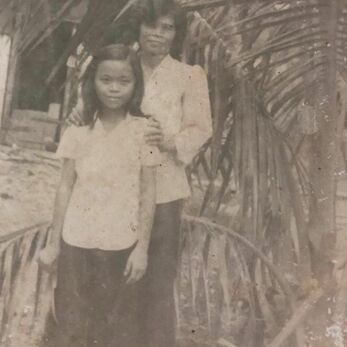

My homeland is my parents working days and nights as teachers and farmers. They did not have a chance to attend university, and I smell the perfume of their dreams for me in the sweat clinging to their worn shirts. Their love of literature was passed on to me in the books my father carefully hand-bound and arranged on a shelf he built.

My homeland is my uncles who fought on opposite sides of the war. One perished as a young man, leaving behind his wife and their baby girl.

Gradually, I learned the importance of the stories found not only in books but in the lives of southerners who had once been strangers to me: a mother who committed suicide by hanging herself from a tree branch because her two sons did not come back from the war; the women in my neighborhood who waited for their men to return from labor camps set up to “re-educate” those who had fought alongside Americans; my classmates who occasionally disappeared from my class, entrusting their lives to the massive oceans with hope of finding a better life; and my neighbors who burned a pile of cash when the government implemented a campaign to drive out capitalists.

My homeland is my uncles who fought on opposite sides of the war. One perished as a young man, leaving behind his wife and their baby girl. The other survived but forever suffered from a deeply wounded soul. Both lost their youth in a war which could and should have been prevented.

My homeland has inspired my fiction and now, in penning my childhood memories, I am reminded of how Vietnamese people, together with the people of many other nations, have survived countless calamities thanks to our determination, ability to work together, sense of hope, and above all, kindness.

In my debut novel, The Mountains Sing, Grandma Diệu Lan, who is a Buddhist, tells her granddaughter Hương: “Our challenges are there for a purpose. Those who can overcome challenges and remain kind to others will be able to join Buddha in Nirvana.”

Article continues after advertisementRemove Ads

The coronavirus pandemic makes me miss Việt Nam but also reminds me that home is where my family is. My home has been Jakarta for the last two and a half years, and soon, it will be Germany where we will be reunited with our daughter. I am blessed to be a person of many homes. During this difficult time, I am inspired by the resilience, discipline and generosity of people around me who are uniting to defeat the coronavirus, so that our entire planet will once again be a safe home for all of us—regardless of our nationalities.

–April 2020

__________________________________

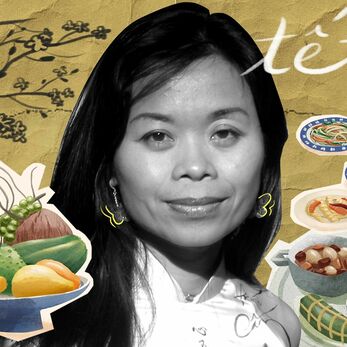

Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai’s novel The Mountains Sing is out from Algonquin.

Article continues after advertisementRemove Ads