Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai on decolonising literature about Việt Nam by writing in the language of the coloniser.

Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai on decolonising literature about Việt Nam by writing in the language of the coloniser.

A few years ago, I visited the New York Public Library and went through its list of tens of thousands of books in English about Việt Nam. I was astonished by how many of the books only focused on Việt Nam as a war, how many were written by Westerners who used Vietnamese people as the background to the Western stories, and how few of the titles were written by Vietnamese writers.

In many of these books, and many Hollywood movies about Việt Nam, Vietnamese women are often reduced to Western stereotypes of Oriental women – exotic sexual objects, helpless victims, absent of trauma, without agency. Viet Thanh Nguyen, the Pulitzer-prize winning author of The Sympathizer, said recently in his commencement speech at Franklin and Marshall College:

I watched almost all of Hollywood’s Việt Nam War movies, an exercise I recommend to no one, especially if you are Vietnamese. Việt Nam was our country, and this was our war, and yet our only place in American movies was to be killed, raped, threatened, or rescued. […] Like many other so-called minorities, we were distorted by stereotypes or erased by ignorance.

This problematic representation of Vietnamese people is a product of colonisation that continues as a destructive mindset long after our liberation from foreign rule. It explains some of my motivations for writing my debut novel, The Mountains Sing, in English. As someone who only had the chance to learn English from the eighth grade, and who didn’t read literature in English until much later in life, writing it felt like climbing a high mountain barefoot. But I was compelled to write in English – the language of invasive military powers and cultures – to directly resist colonialist narratives and attitudes about Việt Nam. I wanted to insert a Vietnamese voice into the canon of literature in English, reclaim the Vietnamese narrative, place Vietnamese people in the centre of the narrative about Việt Nam, assert that Việt Nam is a culture and not a war, and represent Vietnamese women as complex human beings who take active roles in society while being the pillars of their families.

Because language is power, I have been using the Vietnamese language as a subversive weapon, snuck into the English text. I don’t always translate Vietnamese words, giving instead the context needed for the reader to guess the meaning, inviting them to embrace Vietnamese culture, to learn new Vietnamese words, to appreciate the richness, colour, textures and rhythm of our language, and to arrive in Việt Nam not only with their mind, but also with their heart. In The Mountains Sing, the Vietnamese language stands proudly with its diacritical marks, unlike most books in English about Việt Nam, in which my mother tongue is stripped down. In my essay ‘Climbing Many Mountains’, which accompanies the novel, I wrote:

By turning to the first page of The Mountains Sing, you will open the door into an authentic Việt Nam where proverbs are sprinkled throughout daily conversations, where lullabies and poems are sung. You will experience the colours, richness, and complexity of our culture, beginning with our Vietnamese names and language, which appear in full diacritical marks. Those marks might look strange at first, but they are as important as the roof of a home. The word ‘ma’, for example, can be written as ma, má, mà, mả, mạ, mã; each meaning very different things: ghost, mother, but, grave, young rice plant, horse. The word ‘bo’ can become bó, bỏ, bọ, bơ, bở, bờ, bô, bố, bồ, bổ (bunch, abandon, insect, butter, mushy, shore, chamber pot, father, mistress, nutritious).

In choosing to retain the diacritical marks of my Vietnamese name, as well as the names of the 23 major and minor Vietnamese characters, I was refusing the norms of the English publishing industry and, in doing so, might have sacrificed the commercial success and popularity of my novel. But it would be a great disrespect to my language were I to have removed the diacritics, considering how integral they are for the meanings of each of my characters’ names – Diệu Lan, for example, means ‘precious orchid’, Hương means ‘fragrance’, and Tú means ‘refined beauty’.

Colonisation takes many forms. Eliminating or distorting aspects of a nation’s culture or customs for the convenience of a dominating culture is one of them. Thus, I believe it was colonisation that stripped away Vietnamese’s diacritical marks, to serve the eyes and ears of Western readers. Now, it is time for the publishing industry to decolonise literature about Việt Nam and return the diacritics to our language. For that, I salute Algonquin Books, and more than 15 other publishers who have bought the translation rights of The Mountains Sing for joining me in my mission.

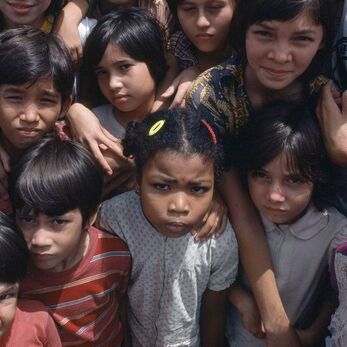

The most powerful enabler of colonisation is dehumanisation, and I have fought to humanise Vietnamese people, along with those from other cultures. In The Mountains Sing, my poetry collection The Secret of Hoa Sen, and my forthcoming novel Dust Child, my Amerasian, Vietnamese and American characters value and celebrate life and cherish their families, just like the people of other nations. Việt Nam is often misunderstood because we are often seen through the lenses of the wars we had to fight in: we were colonised for nearly a thousand years by different Chinese empires, and fought several wars of resistance against the Mongols, before being invaded and occupied by the French, the Japanese, and the Americans. Our colonisers divided our country and our people and tried to reduce us to pitiful victims who didn’t deserve to live. In Hearts and Minds, a 1974 American documentary film directed by Peter Davis, General Westmoreland – former commander of US forces in Việt Nam – showed his colonist and racist attitudes by stating: ‘The Oriental doesn’t put the same high price on life as does a Westerner. Life is plentiful. Life is cheap in the Orient.’

If Westmoreland had met Grandma Diệu Lan and Hương from The Mountains Sing, what would he say of their love for life and the many sacrifices they made for their family? Would he be able to look them in the eyes and tell them that life was cheap for the Vietnamese?

‘Americans, and Europeans, have imagined the Vietnam War as a racial and sexual fantasy that negates the war’s political significance and Vietnamese subjectivity and agency,’ said Viet Thanh Nguyen, regarding the popular Broadway musical Miss Saigon, in which the main Vietnamese character Kim is portrayed as sexual and desperate. Kim suffers silently, has no agency, and longs for an American G.I. to save her. When she finds out she cannot live in America, she commits suicide: ‘For her,’ Diep Tran said, ‘being dead is better than being Vietnamese.’

In Dust Child, readers will meet Trang and Quỳnh, two sisters who contradict the image of Kim in Miss Saigon. Trang and Quỳnh did not rely on their American boyfriends to save them; they take charge of their own destinies. Though Trang is a bar girl and a sex worker, she writes her own poetry, loves to read, and can recite from memory sections from Nguyễn Du’s The Tale of Kiều, an epic poem containing 3,254 verses. Dust Child depicts how trauma resulting from war, violence, discrimination, abuse, and abandonment affects Vietnamese, American and Amerasian children who were born into relationships between American soldiers and Vietnamese women. More importantly, it shows the courage of individuals trying to break away from the cycles of intergenerational trauma and offer healing to themselves and to those around them.

The road to decolonising literature in English about Việt Nam is long and arduous but I am not alone. I stand beside Vietnamese and diasporic Vietnamese writers who are doing extraordinary work in correcting misperceptions about Việt Nam and our people; I stand beside our readers, booksellers, and literary champions who are uplifting my work and sharing it with enthusiasm. It gives me hope for a future in which all cultures and ethnic groups are respected for who we are and have the freedom and the right to share our stories, without the need to modify any aspect of our storytelling to serve another group of people.

Born and raised in Việt Nam, Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai is the author of the international bestseller The Mountains Sing, runner-up for the 2021 Dayton Literary Peace Prize, winner of the 2020 BookBrowse Best Debut Award, the 2021 International Book Awards, the 2021 PEN Oakland/Josephine Miles Literary Award, and the 2020 Lannan Literary Award Fellowship for Fiction. She has published twelve books of poetry, fiction and non-fiction in Vietnamese and English and has received some of the top literary prizes in Việt Nam including the Poetry of the Year 2010 from the Hà Nội Writers Association. Her writing has been translated into twenty languages and has appeared in major publications including the New York Times. She has a PhD in Creative Writing from Lancaster University. She was named by Forbes Vietnam as one of 20 inspiring women of 2021. Her second novel in English, Dust Child, is forthcoming in March 2023. For more information, visit: www.nguyenphanquemai.com

Photo credit: Tapu Javeri