Trauma is a root cause of many Vietnam veterans rejecting their Amerasian children, those from relationships between women and soldiers.

I am writing this just after a video call in which I translated a tearful reunion between a 52-year-old woman and her father. For many years, the woman had searched for him, but the father did not know she existed. By the miracle of DNA testing, they found each other.

During their reunion on the video call, their tears and their laughter seemed to bridge the physical distance of 8,600 miles between them: The father is a U.S. military veteran who lives in Ohio, and the daughter lives in southern Vietnam.

Their story has a happy ending, unlike most stories of Amerasians born during the Vietnam War from relationships between American soldiers and Vietnamese women.

The fathers of the Amerasians called 'bui doi,' the dust of life

For many years, as I assisted Amerasians and their parents in their search for each other, I saw so much heartbreak and so much hope for healing that I was compelled to write my latest novel, "Dust Child."

Opinions in your inbox:Get exclusive access to our columnists and the best of our columns

My novel opens with the voice of Phong, a Black Amerasian who was born in 1972. Like many thousands of Amerasians, Phong, who was abandoned when he was a baby, is illiterate and had to spend years of his life on the street, homeless.

Even though his name, Nguyen Tan Phong, means strength from a thousand gusts of wind, people call him “bui doi,” the dust of life, and consider him unworthy. Through this novel, I want to present Phong in his full human complexity, and as a human being who deserves love and respect, because he is not a victim: He is a survivor, a carpenter, a musician.

About 100,000 Amerasian children were born during the war from relationships between Vietnamese women and American soldiers. Like many of these Amerasians, Phong does not know his parents and spends his life searching for them, with little hope. Yet he is determined to break the cycles of intergenerational trauma and offers healing not only to himself and his family but also to those around him.

Healing also is much needed for fathers of Amerasians who are willing to reconcile with their past. They were among the nearly 3 million U.S. servicemembers who served in Vietnam from 1965 to 1975. Most were young men, and many remain traumatized today.

PTSD and and survivor's guilt:50 years later, peace treaty that was supposed to end Vietnam War still haunts my family

What Vietnam War veteran wants you to know:After a month in Ukraine, this 77-year-old has a message for his fellow Americans

Trauma is a root cause of many veterans rejecting their Amerasian children when they are contacted. Yet some have returned to Vietnam, in the hope of finding the women and children they abandoned.

In assisting those men in their search, I have seen their regrets and their strong wish to make up for their past mistakes. I feel a special connection with them because I can see into their humanity: Since 2009, I have been translating literary works by American writers who once fought in Vietnam, facilitating literary exchanges between them and Vietnamese writers.

I also have family members who fought on opposite sides of the war. Born in Ninh Binh, in northern Vietnam, I was just 2 years old when the war ended in 1975. However, growing up in both the north and the south, I've learned to embrace stories of people from all sides of the war, and I'm determined to employ literature to foster empathy, healing and reconciliation.

My conversations with fathers of Amerasians as well as with other American veterans over the years helped me build the world of my book character Daniel Ashland, who was a helicopter pilot during the war – and who is so transformed by the violence he witnessed and participated in that he at first walks away from his unborn child, but then years later comes back to Vietnam, hoping to find his son or daughter.

The mothers of Amerasians: Their voices matter

In "Dust Child," Dan’s trauma severely affects his relationship with his former Vietnamese lover – Trang, who represents hundreds of thousands of real Vietnamese women working in bars and brothels that served U.S. soldiers during the war. The voices of these women matter because their stories are little known.

From my interviews with these women in real life, I saw the depth of their sorrow, their trauma, as well as the social ostracism they have had to face from a conservative Vietnamese society.

'You're my Kim':How I landed a Hollywood movie and gained a 'Heaven and Earth' family

I was 15 when the first U.S. Marines landed:'On the Ho Chi Minh Trail' takes me back to my days fighting in the Vietnam War

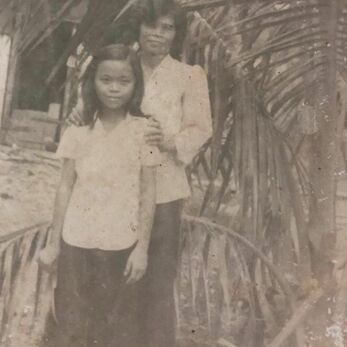

I will never forget my long conversation with a woman who is nearly as old as my mother. She had contacted me after I had written a news article about American veterans who returned to Vietnam to look for the pregnant women whom they abandoned.

I had asked one of the veterans to write a letter to his ex-Vietnamese girlfriend explaining to her why he had abandoned her – and why he is now back looking for her. I had translated the letter and published it in Tuoi Tre, a national newspaper in Vietnam, together with my article featuring the veterans’ desperate searches.

When the woman contacted me, she spoke on the phone for 15 minutes, asking many questions about myself before revealing that she was the one in the letter. She had worked in a bar, had been pregnant with the veteran’s child and had to give the child away to an orphanage. She told me that even then, she thought about her child every day, with regret and sorrow. She had done DNA tests and tried to search for her child but without success.

"Dust Child" is, in part, my fight against the misrepresentation of Vietnamese women who had to work in bars or brothels during the war. In many Hollywood movies and books in English, they are reduced to the stereotypes of Oriental women, exotic sexual objects, helpless victims, with no trauma, no agency. It is not often that they are given a voice but instead appear as background in stories of Western men who are depicted as their saviors.

This novel is also my fight against the sexism and racism that still exist within my own Vietnamese community. It is a tribute to the courage of Amerasians and their mothers, and those American veterans, who, despite their long-lasting trauma, have reached out to assist others and offer healing.

I wrote this book – fittingly being published on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the U.S. withdrawal of combat troops from Vietnam – to offer my prayers for a world where there is more compassion, more peace, more forgiveness and healing.

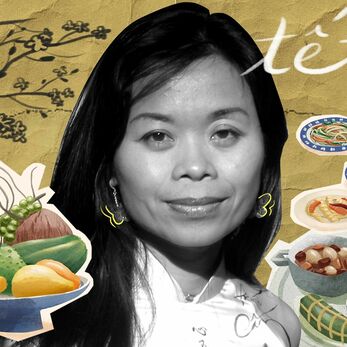

Nguyen Phan Que Mai, executive producer of "Intersections," an award-winning documentary series about Amerasians, is the author of the internationally bestselling novel "The Mountains Sing" as well as the novel "Dust Child," coming out on Tuesday. Follow her on Twitter: @nguyen_p_quemai

More on the Vietnam War:

'Homeless among the clouds': My journey from movie star to faceless fall of Saigon refugee

‘Remembrance is vital for our society’: Honoring 40 years of the Vietnam wall

Fall of Kabul, fall of Saigon: Their horror was our horror. Anguished, we pray for a miracle.