Saigon’s guide to restaurants, street food, news, bars, culture, events, history, activities, things to do, music & nightlife.

Every year, as the pages from my block calendar peel off, bringing me towards another Vietnamese New Year, my mind once again fills with nostalgia about an old Tết. Tết in my memory begins with my childhood in a small house nestled under a coconut grove on the outskirts of Bạc Liêu in the Mekong Delta. Those were days of hardship, yet my parents worked hard so that Tết could bloom magnificently for all of us.

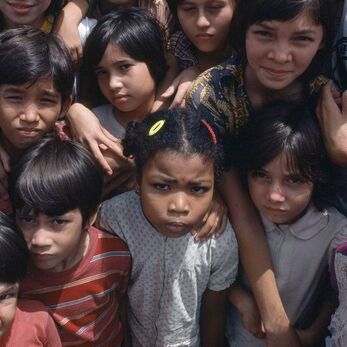

Born into the Year of the Buffalo (1973), I grew up during a time when poverty was common among Vietnamese people. Those who survived the war struggled to make ends meet. Everyone I knew didn’t have much to eat all year round, and children had to do all types of odd jobs to help put food on the table. Like all my friends, for the entire year I looked forward to Tết because it was the only time when we could eat good food and receive a new set of clothes, and even some lucky money.

A time to shed old leaves and apply new paint

In my memory, Tết preparations started months before the lunar year’s end. In September, my father tended our pond to make sure that our fish would be ready for Tết. We planted chilies, onions, cabbages and leafy vegetables, which my mother and I would bring to the market to sell in order to buy the many necessities for our celebrations: pork, dried green peas, sticky rice, dried shrimp, fruit, firecrackers, and offerings for the ancestors’ altar. If we were lucky, there would be enough money left for my parents to buy each of us — their three children — a new set of clothing.

A few weeks before Tết came, my father studied the weather patterns, talked to his friends and decided on the day to pluck the leaves of our apricot tree, mai. I watched in amazement as the barren tree started to sprout countless green buds which grew fuller and fuller as Tết drew nearer. My father monitored the watering and fertilizing of his tree every day to ensure they bloomed at the exact right time. As was true of the peach flowers we used to have in the north, if our mai blossoms bloomed brilliantly during the first day of Tết, our family would be blessed for that entire new year.

Regardless of how poor we were, Tết was the time to look and feel good, so every year, about two weeks before it arrived, we scrubbed and painted our house. My brothers and I moved our wooden and bamboo furniture out to the front yard and gave it a good wash, splashing water at each other while we worked. We then crawled into our most tattered clothes and covered our walls with a white paint we mixed ourselves using limestone powder and water. We laughed and joked while we worked, feeling happy as the gleaming white spread under our hands.

A family in Sa Đéc in the Mekong Delta with rows of apricot trees that are stripped off old leaves. Photo by Andy Ip.

After the house was scrubbed and cleaned, I spent hours helping my mother prepare a special pickled dish using onions and scallions we bought at the market. They had to be fresh, still attached to their leaves and roots. More importantly, they had to be bite-size. Bringing them home, we washed any dirt and mud away, then soaked them overnight in water diluted with ash I collected from our cooking stove (we cooked mostly with rice straw or tree branches during those days). The ashy water helped tame the onions and scallions so that the next morning they no longer made my eyes weep when I peeled off their outer layers to reveal their glistening whiteness. Sitting side-by-side with my mother in our front yard, I talked to her about our plans for the New Year, about the food we would cook, and whom my parents had chosen to be the first person to step into our house on the first day of Tết.

Many hours of squatting on low stools to prepare our pickled dish always made our backs sore, but as we spread the peeled onions and scallions out on thin tin trays to dry them in the sun, we felt happy to watch the white alliums grin back at us. They looked like flowers that had sprung up from the earth, like the purest type of beauty. While waiting for them to dry, I gathered small twigs to start a fire in our kitchen while my mother measured and mixed vinegar, sugar and salt into a pot.

Once it cooled, we poured the pickling liquid over our onions and scallions, which we had arranged artistically into glass jars. From time to time, I would help my mother carry these jars out to the sun, to make sure that our pickled onions and scallions would "ripen" in time for Tết. They always made the perfect side dish, to be savored with dried shrimp, sticky rice cakes, and boiled or stewed meat; their fragrant sour-sweetness melting in our mouths.

The week before Tết was the busiest, but also the happiest. One of the most exciting events was to drain our pond to harvest our fish. We had no motorized pump back then, only a bamboo bucket we connected to two strong ropes and took turns swinging to get the water out of the pond. Our hands would grow tired and hours passed before we saw fish jumping up and down, trying to escape the increasingly shallow water. Our pond was not large, but large enough to reveal different secrets each year. Besides the tilapia fish my father farmed, we also often found mullet, catfish and perch.

For quite a few years, I was not allowed to go into the drained pond to catch fish with my two elder brothers. Standing on the pond’s bank, I burned with jealousy as I watched my brothers jump around in the mud; their faces blackened, their teeth gleaming in the sunlight as they cheered and laughed. Each time a fish was captured they would scream with excitement, lift it high into the air while it wiggled madly, and then throw it on the floor.

My job was to scoop the jumping fish into a bamboo basket and release it into a large tin bucket filled with water. Sensing that I was unhappy, my parents would tell me that catching fish with your bare hands was not a task for a small girl like me. Of course, they were right. My brothers’ hands were often injured. One year, a catfish pierced its sharp thorn into my brother’s finger. He ran into the house and when I found him half an hour later, he was under his bed, clutching his hand to his chest, crying like a baby. I laughed at him so hard, but a few months later, I too was stung by a catfish’s thorn. The pain pierced into my bones, so hot, deep and searing, that I could not help but crawl under our bed and bawl like a newborn as well.

Candied coconut by any other name

Tết would not be fully ready without mứt dừa, a type of candied coconut ribbon. As someone with "monkey genes" who could climb well, I was tasked with the responsibility of picking several fresh coconuts from our trees. Our small garden was filled with fruit trees, and my favorite were the coconut trees that spread their protective arms over our house, singing us lullabies by rustling their green leaves against our tin roof. These coconut trees bore plenty of fruit all year round. I quickly got up to the top of a tree, leaned my body against the biggest leaf and selected the coconuts which gleamed with several golden stripes on their dark green skin. The flesh of these coconuts would be perfect: not too thin and not too crunchy. Hanging on to the tree with one hand, my other hand would swing a sharp knife to chop the chosen coconuts from their stems. They made happy thumping noise as they kissed the ground.

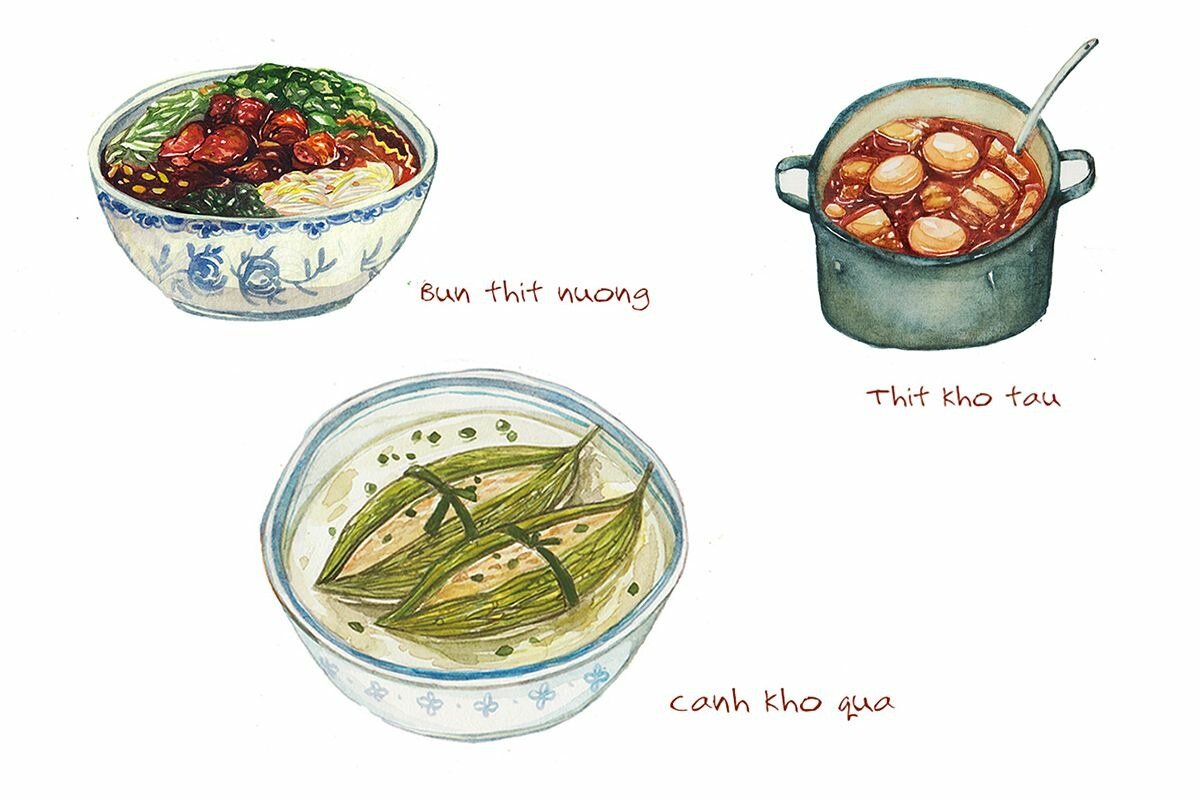

Just like catching fish for Tết, preparing candied coconut ribbons was a joyous family event. My father and brothers chopped and then peeled away the thick outer layers of the coconuts. We then drilled holes through the hard shells, tilting the fragrant juice into a large bowl. Later, my mother would reward each of us with a glass of delicious coconut water. The rest we would be put aside to make thịt kho trứng — pork and eggs stewed in coconut juice — an essential Tết dish that's common in the Mekong Delta.

Braised pork and bittergourd soup are two popular Tết dishes. Illustration by KAA Illustration via Behance.

Making candied coconut ribbons was fun, but it was also a test of our skills and patience. After separating the white coconut flesh from its hard shell, we peeled the brown, inner-skin away, then shaved the coconut flesh into thin, long ribbons that we dipped into hot water. After draining them, we mixed them with white sugar. Our neighbors often added food coloring to make red, pink and even green coconut ribbons, but we preferred ours to be white and natural.

After a few hours, when the sugar had completely dissolved into the ribbons, I would make a low fire in the kitchen for my mother to cook the coconut ribbons in a large frying pan. To help the sugar crystallize, she occasionally stirred the ribbons with a long pair of chopsticks, giving them an equal amount of heat while not breaking them. My job was to keep the fire very low, so as not to burn my favorite Tết dish. It was the most delicious job as I only needed to put out my tongue to taste the sweetness of Tết in the air. About an hour later, we would have a basket full of long, curly coconut ribbons, crystallized in their fragrance.

The craft behind bánh chưng

As the mai tree’s golden flowers started to bloom, a breeze would sweep across nearby rice fields and waft to my nose, whispering that Tết was about to knock on our door. With this aroma in the air, we made traditional sticky rice cakes, or bánh chưng. Bánh chưng is a must-have for northern Vietnamese during Tết. My parents, who had uprooted themselves from the north and planted themselves into the soil of southern Vietnam during the late 1970s, embraced their northern heritage by making bánh chưng every year while our southern neighbors prepared bánh tết.

Both of these sticky rice cakes use the same ingredients, including sticky rice, dried green peas and pork. However, bánh chưng is wrapped with lá dong (phrynium leaves), which grow abundantly in the north, while bánh tết is wrapped with lá chuối (banana leaves) which you can find anywhere in the south. In addition, bánh chưng is square and thick, while bánh tết is long and round. Lastly, while bánh tết can have a “sweet” version (made with sweetened bananas), bánh chưng only has a savory version that includes pork and green peas.

The night before the important day of making our bánh chưng, I helped my mother soak dried green peas overnight to remove their skin. We also soaked sticky rice and separated good grains from the brown and yellowish ones. My brothers squatted in the yard as they helped my father split bamboo stalks into thin, flat strings. These strings would be used to tie the leaves around our cakes. My mother explained that bánh chưng needed to be boiled for hours, so plastic or nylon strings would not be healthy.

Once these tasks were complete, my father would ask me to help him cut down lá dong leaves from our garden. When we moved south, he searched all over for dong plants, which were hard to find and harder to grow in the tropical climate. With these plants growing in our garden, we felt we had brought with us a part of our ancestors’ village. We cut the precious leaves from their stems, piled them up gently, and brought them to our yard to wash away any dirt and insects. We took care so that no leaf was torn. Softening them under the sun or over hot coal, we set them aside.

On a large working area, my mother spread out a clean, large straw mat. Onto the center of the mat we placed the dong leaves, bamboo strings, bowls of the drained sticky rice, dried green peas and marinated pork. As we had no fridge, my mother had to wake up at five that morning to go to the local market to buy the best pork available. It needed to be fresh, with a precise balance of lean meat and fat. Bringing it home, my mother washed and cut the pork into large pieces, then marinated it with freshly ground pepper, fish sauce and salt.

One of the extraordinary things about my father is that except for boiled or fried eggs, he can’t cook, yet is a master at making bánh chưng. While my mother, brothers and I struggled to form our bánh chưng into square shapes, using wooden molds to guide us, all my father needed was his bare hands.

He started by arranging several lá dong leaves on to the mat and placing a layer of sticky rice, green peas and marinated pork on top, which he then covered with another layer of green peas and sticky rice. Covering his artwork with several more lá dong leaves, he folded the four sides, tugging the leaves into each other so that they made a perfect square. He then tied the square cake with the bamboo strings he had made with my brothers.

Tranh Khúc Village in Hanoi is known for their special bánh chưng.

My father explained that the strings had to give space for the rice and dried green peas to expand when they cooked. Yet they had to be tight enough for the rice not to spill out. He said that in northern Vietnam, where the weather was cold around Tết and families didn’t have refrigerators, bánh chưng would be released immediately into deep wells after they were cooked. Resins from the lá dong leaves, once meeting the cold water, would form a thick protective layer over the cakes. The wells would act as refrigerators, keeping the cakes fresh for weeks.

My father was so famous for his bánh chưng-making skills that many of our relatives and friends often asked us to make bánh chưng for them. While there was a lot of work involved, we did not mind since it would be more economical to make and boil over 30 bánh chưng at one time, sufficient for seven families and for the entire duration of Tết.

After we were done with wrapping the bánh chưng, my mother took out a gigantic pot that she had borrowed from our rich neighbor. The pot was large and expensive, thus in our whole neighborhood, there was only one family who could afford it. Families took turns borrowing the pot to boil their bánh chưng and bánh tết. The owner was happy to lend it because although we were financially poor, we were rich with generosity towards each other.

For the boiling of bánh chưng, my brothers dug a hole in a corner of our garden and my father started a fire with the biggest logs he could find. It takes up to 10 hours for the bánh chưng to cook, and therefore, this was the only time all year that my brothers and I were allowed to stay up all night to look after the fire. We huddled against each other in the dark, telling scary ghost stories that made us giggle and huddle even closer to each other. In the early morning, we scooped out the small bánh chưng, which we wrapped ourselves, and had them for breakfast. They tasted delicious, even though they looked shameful compared to my father’s perfectly square cakes.

The last night of the year

My father knew a lot about bánh chưng because he is the eldest son of my grandparents. He also knows a lot about the rituals of worshiping ancestors because Vietnamese ancestors are believed to "follow" the eldest son from north to south. On the last day of the old year, my father carefully cleaned the family altar and arranged a special display, which included an incense bowl, a pair of bánh chưng, fresh flowers, a bottle of homemade rice liquor, and fruits of many colors. My mother and I cooked special Tết dishes, such as boiled chicken, glass noodle soup, steamed fish, stewed pork and eggs, fried vegetables, and orange gấc sticky rice.

We offered our food to our ancestors around 5pm on the family altar, and after allowing our ancestors to "eat" this sumptuous meal for several hours, we gathered and enjoyed the best food of the year. The cutting of my father’s bánh chưng was a ceremony by itself; after untying the bamboo strings and peeling away the outer leaves, we arranged the strings across the cake’s green surface. Turning the cake upside down, we held the two ends of each string, pulling them towards each other, thus cutting the bánh chưng into square or triangle pieces. The taste of my father’s bánh chưng still remains in my mouth today; fragrant and savory. It tasted perfect, together with the pickled onions and scallions which my mother and I had prepared.

After cleaning up, I would clutch my mother’s hand as we walked to a nearby pagoda. Holding burning incense in front of my chest, my eyes closed, I would pray to Buddha to bless me with lots of lucky money that year. As I was never given any pocket money during the rest of the year, Tết was my only chance to gather savings, which I kept in a clay pig on my bookshelf. If I had enough lucky money, I would be able to buy a new book.

Returning home from the pagoda, I would see that my brothers had hung our firecrackers on our front door, anxiously waiting for the time to set them on fire. I wish I had joined them then, because firecrackers would be banned a few years later, hence the disappearance of this long and special tradition. But at that time, I helped my mother as she hurried to set up a tray of offerings, laden with fruit, flowers, liquor and incense. I carried the tray with her to our front yard and lit the incense. Watching how long my mother prayed to heaven, I sensed how important this ceremony was to her and to our family. I felt that all the gods were coming to join us, and my ancestors were also present.

Chúc mừng năm mới

Finally, the New Year approached with the faint sounds of firecrackers from far away, then moving closer and louder towards us. My two brothers would fight for the right to ignite the firecrackers, while I stood, frozen in fear, my hands over my ears.

We woke up very early the next morning, with yellow mai flowers brightening our living room. Smoldering incense filled my senses, and my happiness soared. Firecracker remnants rested like a blanket of pink and red on our front yard. We were not allowed to sweep anything away during the entire first day of the New Year, so as not to chase our luck away. I admired this red and pink carpet all day as it was twirled up by a dancing wind or rested peacefully under the gold, yellow and white chrysanthemum and mai flowers.

I put on my new set of clothes for Tết that I had wanted all year long, while my brothers burned left-over firecrackers in our front yard. When my parents were ready, they called us into the house, handing each of us a red envelope containing our lucky money. We would bow our heads, wishing them health, luck, success and happiness, before busting out of the house, waving the red envelopes on our hands.

But we were not allowed to go into any neighbor’s home unless we were specially invited. One's luck for the whole year depended on the fortune and character of the first person to enter one's home on the first day of the New Year. My father often chose a senior neighbor whose children were successful and who had a gentle and cheerful personality. The neighbor would often come before 7am on the first day of Tết, bringing my parents lots of good wishes and a red envelope for me, since I was the youngest member of the family.

During Tết, families in Saigon gather at flower markets to pose for photos, buy new plants for their home, or just simply to soak in the festive ambiance.

Around noon our house would be filled with greetings from relatives and neighbors. Everyone visited the house of everyone else in the neighborhood. We served our visitors green tea and candied coconut ribbons. Our family members took turns visiting the houses of relatives and friends, making sure that someone was always home to greet and take care of unexpected visitors. Snacks and food were served around the clock.

All the food my mother and I had spent many hours preparing came in handy; even though we were discouraged by traditions from cooking during the first day of the New Year, we could always serve our guests a good meal with our bánh chưng, stewed pork in coconut, as well as pickled onions and scallions. When the cooking resumed on the second or third day of Tết, we would make sweet and sour soup with our fresh fish, and serve our guests the ripest vegetables from our garden. From our home flowed an endless river of chatter and laughter, while I would occasionally sneak into my parents’ bedroom to count how much lucky money I had received.

Thinking back, I realize that my parents were very strict in raising me and hardly ever showed their emotions during our daily lives. It was only during Tết that I saw their tender sides. Tết also allowed me to be a bit naughty and not be scolded or punished, and it allowed me the rare privilege of accompanying my parents whenever they visited their friends.

Many Tếts have gone by, though my memories from one particular Tết remain vivid. My mother had taken me to visit one of her good friends who lived on the other side of the rice fields from us. I remember the vast rice fields spreading their green arms out towards the horizon as we walked. The sun was setting, tilting light onto my mother’s long, black hair. Flocks of white cranes rose up, dotting the blue sky with their flapping wings. We walked among the singing of rice plants and the perfume of a spring that embraced us from all directions. I wished then that I could go on like that forever and ever beside my mother.

These days most Vietnamese families, including my own, no longer celebrate Tết the traditional ways due to all the demands of modern life. Still, regardless of how busy we are, we set aside time to enjoy Tết with our loved ones. Families are united for Tết, and friends who may not see each other for the rest of the year will meet and enjoy a meal together. Perhaps Tết is important for all Vietnamese because it reminds us of how happiness can derive from our cultural heritage, and how wonderful it is to stop running after our material desires, at least for a few days, and enjoy what we already have.

Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai is the internationally best-selling author of The Mountains Sing, and the forthcoming novel, Dust Child (March, 2023). She has received many literary awards in Việt Nam and internationally, including the Lannan Literary Awards Fellowship for a work of exceptional quality and for its contribution to peace and reconciliation. A version of this article was originally published in Vietnam Heritage.